After Communism: Lessons from Poland on Reform, Memory, and State-Building

A week in Poland reshaped how I think about economic change, political leadership, and the slow work of building real institutions

I recently returned from Poland, where I spent a week attending The 89 School, a summer program focused on how the country transitioned from communism to democracy and a market economy. Over seven days, we visited key sites in Warsaw and Gdansk, met reformers, and explored what it takes to build legitimate institutions after authoritarianism.

We began at the Palace of Culture and Science, a towering relic of Stalinist ambition. Once the tallest building in Warsaw and long a symbol of Soviet dominance, it has since been reclaimed by the Polish people. Today it houses restaurants, cinemas, offices, and public events, and is surrounded by modern skyscrapers. It has been absorbed into the city’s daily life through a mix of irony, debate, and deliberate reinterpretation.

One of its many uses today is as a conference venue. We met in the Rudnev Room, named after Lev Rudnev, the Soviet architect who designed the building. It was a fitting place to start. Our first session traced how communism was imposed on Poland in 1945 after World War II—not through revolution, but by Red Army occupation, Moscow-backed institutions, and the dismantling of Poland’s prewar elite. The Palace may have been a “gift,” but the cost was clear: repression, propaganda, and the erasure of national autonomy.

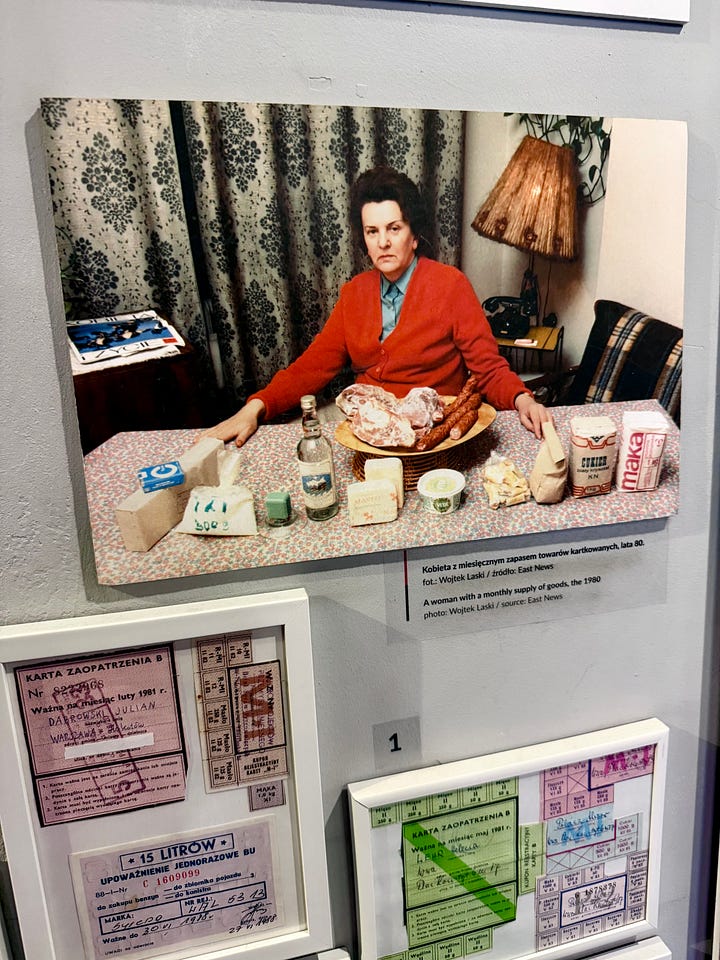

Later that day, at the Museum of Life Under Communism, the illusion cracked further. While the Palace projected abundance, the museum revealed the reality: queues, ration cards, cramped kitchens, and daily improvisation. One offered spectacle, the other substance. One broadcasted power, the other captured its cost. Together, they told a story not of success, but of Polish struggle and survival under communism.

On day two, we visited the Chancellery of the Prime Minister and the Polish Parliament. This was architecture of a different kind, one designed for democracy. The atmosphere was formal but accessible, reflecting Poland’s conscious choice after 1989 to turn away from centralized control. Though we didn’t observe any meetings or debates, the openness of these institutions was clear. Poland’s decision to adopt a parliamentary system was rooted in its desire to prevent any single party or figure from dominating the state again.

Days three and four brought us to Gdansk. Just a three-hour train ride north of Warsaw, we began our first day in Gdansk at the shipyards and the museum where the Solidarity movement began in 1980. Near the entrance to the European Solidarity Centre, the 21 demands are still posted at the gate. They were tangible: free unions, paid leave, basic dignity. Inside, we traced how workers and intellectuals formed an unlikely alliance that challenged and ultimately dismantled the communist regime. At the center was Lech Walesa, a shipyard electrician and longtime activist who gave the movement moral weight at home and drew global attention. Gdansk felt different from Warsaw. Where Warsaw carried the weight of reconstruction and governance, Gdansk felt rooted in labor, community, and moral resolve.

The next day, we joined a workshop led by Prof. Bogna Gawrońska-Nowak on the political economy of Poland’s transition. We stepped into the shoes of the 1989 reformers, debating the trade-offs they faced: liberalize prices quickly or slowly? Privatize now or wait? How do you protect social cohesion when inflation hits and jobs vanish? The session made one thing clear, transformation wasn’t just about designing the right policies. It was about timing, risk, and moral responsibility. Poland’s success required more than technocrats. It needed leaders with the courage to act, and the credibility to bring the public with them.

Back in Warsaw on day five, we met Leszek Balcerowicz, the former politician and economist behind Poland’s post-communist radical economic reforms labeled as shock therapy. “Inflation had reached 500 percent. The country was bankrupt,” he told us. “You cannot put out a fire slowly.” So when the window opened, he acted quickly: liberalizing prices, tightening the budget, reforming the currency, and opening to international trade and investment. But what stood out wasn’t just the urgency, it was how prepared he was. During communism, Balcerowicz had spent years quietly developing reform plans with a small group of economists.

That preparation and acting decisively paid off. Today, Poland is widely seen as one of the most successful post-communist economies in Europe. Since 1989, its GDP has multiplied more than tenfold, poverty has dropped, and exports—from cars to IT services—have surged. EU membership in 2004 accelerated growth, investment, and infrastructure, and Poland famously avoided recession during the 2008 global financial crisis. It now has the largest army in the EU, a growing middle class, and one of the most productive workforces on the continent.

On day six, we visited the Museum of Modern Art. Since its opening in 2024, the building has drawn controversy for its stark, minimalist design and uneasy fit with its surroundings. From the outside, it feels understated, even out of place. But step inside, and the architecture begins to speak: its wide windows frame a perfect view of the Palace of Culture and Science. That framing felt intentional. Where the Palace once projected Soviet power, it now appears as an object of reflection—seen, not feared. Through art and architecture, Poland didn’t erase its past. It reframed it.

As you may know, I live in Canada now and work on development issues in Belize. These are very different contexts, but the Polish experience offered lessons that travel well. Real transformation doesn’t come from momentum alone. It requires legitimacy, lasting institutions, and people ready to lead when systems break down. Poland had that in 1989. Its alternative elites—shaped in unions, universities, churches, and underground networks—were prepared when the moment arrived. They weren’t just critics of the old system. They carried the moral authority, technical skill, and public trust needed to build something new. Leaders like Walesa and Balcerowicz.

Belize, with its reliance on external funding and fragile institutions, lacks this kind of depth. Since its independence in 1981, power has rotated between a small circle of political elites, with each side focused on short-term wins rather than building lasting capacity. Too many projects chase election cycles or donor timelines, leaving little behind when priorities shift. What’s needed isn’t more plans, but system builders—people and institutions that can outlast politics, earn public trust, and slowly build the foundations for reform that lasts.

Canada faces a quieter crisis. On the surface, institutions seem to function well, but too often the system settles for maintenance over ambition. Beneath the facade are structural problems: sluggish economic growth, declining productivity, underinvestment in innovation, and record outmigration to the United States. In the country’s largest city, Toronto, mockingly dubbed "the city of pilot projects," leaders wait for others to go first. Politicians manage instead of lead. The result is drift: eroding trust, sidelined ambition, and stalled momentum.

What Poland achieved wasn’t just market liberalization. Its real accomplishment was sequencing: acting boldly but not blindly. Privatization came only after institutions were in place, peaking roughly five years after the 1989 reforms began. This gradual approach helped prevent the kind of oligarchic takeover seen elsewhere and created breathing room for new ventures to emerge. By the mid-1990s, thousands of private firms had emerged, not by inheriting old state assets but by building new value within a rules-based system.

On our final day, we returned to the Palace of Culture and Science, this time not to study its history, but to reflect. Once again seated in the Rudnev Room, we looked back on the week: from Warsaw’s postwar architecture to Gdansk’s labor movement, from shock therapy to memory politics. What stood out was how Poland managed to balance radical change with continuity, and how the presence of alternative elites helped steer the country through uncertainty.

The most important thing I took from Poland is that real change isn’t about slogans. It’s about structures that endure—and about knowing when to move fast, when to go slow, and when to keep the past in view so a different future can be built.

Sounds so interesting!!!