Krismos Bram, Sambai, and the Challenge of Framing Belize’s Creole Culture as an Experience

Why Creole culture has been harder to define for visitors

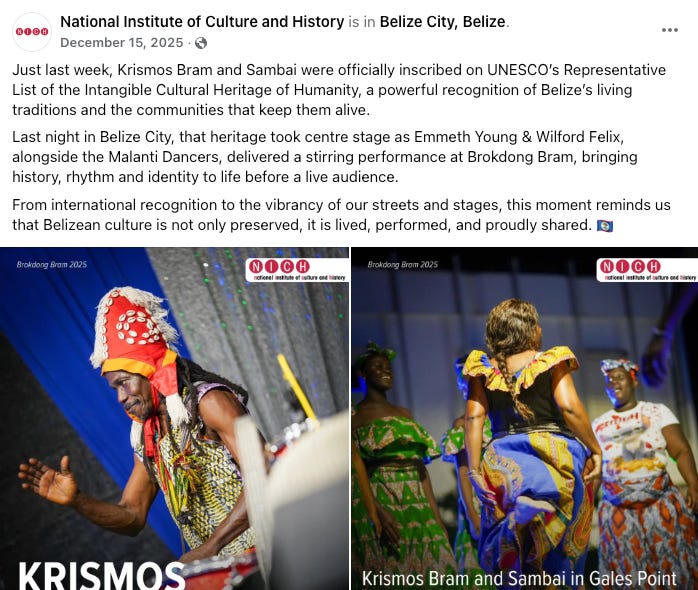

When Belize’s Krismos Bram and Sambai were added to UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, it caught my attention for a reason that had less to do with UNESCO and more to do with Belize.

Many Belizeans, myself included, haven’t experienced these traditions firsthand or fully understood where they come from. That’s not because they’re obscure or fading. It’s because they’re primarily practiced in places most people don’t go.

Belizeans know Creole culture very well. We eat it every day, and religiously on Sundays. We hear it on the radio. We speak it daily. Yet when it comes to how Belize presents culture, Creole culture sits in an awkward position. It is widely practiced, but seldom presented as a cultural experience for visitors in its own right.

From Tradition to Experience

Belize has been relatively successful at turning culture into something visitors can understand and seek out.

Maya culture is presented through archaeological sites, village visits, and lived experiences. Tourists are taken to places like San Antonio Village to learn how corn is ground, tortillas are made, and how daily life operates. These are structured encounters with living culture.

Garifuna culture has followed a similar path. Villages like Hopkins, Dangriga, and Seine Bight are positioned as cultural anchors, and elements of Garifuna music and drumming are intentionally brought into hotels, resorts, bars, and festivals in places like San Pedro, Placencia, and San Ignacio. Even when visitors aren’t traveling to Garifuna villages, they’re still being introduced to Garifuna culture in a way that’s legible and memorable.

This didn’t happen by accident. These cultures were easy to frame because they are anchored to specific places, and then extended beyond those places.

Creole culture never quite fit that model.

The Problem with Being Everywhere

The challenge is that Creole culture cuts across districts and communities in Belize. It shows up in language, humour, food, music, and social norms. You don’t travel to it. You’re already inside it the moment you arrive.

That omnipresence has always been a strength, but it has also made Creole culture harder to frame as something distinct from a tourism perspective. There’s no obvious entry point, no single place to send people, no clear experience to point to and say, “start here.”

As a result, Creole culture has remained the backdrop of Belize rather than something intentionally highlighted.

Gales Point as a Starting Point

UNESCO’s recognition of Krismos Bram and Sambai gives Creole culture something it has rarely had: a clear anchor.

That anchor is Gales Point Manatee, where geographic isolation helped preserve highly visible Creole traditions rooted in rhythm, movement, and community participation. Sambai and Krismos Bram survived there because the village itself remained intact.

This contrasts with Belize City, where Creole culture is dominant but developed through sustained contact with British colonial institutions and other cultures present in the city, resulting in a more layered and adaptive expression.

From a tourism and cultural strategy perspective, that distinction matters. Gales Point shows what Creole culture looks like when preserved through isolation. UNESCO’s recognition creates an opportunity to start there, then extend the story outward.

Extending the Experience Across Belize

My suggestion is to use Gales Point as an anchor for Creole cultural experiences and, over time, extend it across Belize.

Belize already has a model for how this works. Garifuna drummers don’t only perform in Garifuna villages. They are invited into resorts, festivals, and cultural spaces across the country. Maya cooking classes are taught in villages, but also referenced and adapted elsewhere. In fact, Maya-themed food nights are common in many popular hotels and restaurants.

Creole culture could be approached in a similar way.

That might mean:

Positioning Gales Point and other Creole communities as cultural destinations, not just places people pass through;

Structured Creole food experiences that go beyond “try rice and beans”;

Storytelling and music presented in hotels and public spaces, with context rather than as background; and

Creole traditions referenced intentionally and seasonally, rather than passing quietly.

None of this requires inventing anything new. It requires naming, framing, and repeating what already exists. And when culture is framed intentionally, rather than taken for granted, it allows the people connected to it to receive more of the tourism benefits.

P.s. I want to acknowledge and thank Gales Point, community groups, non-profits, and NICH for sustaining, sharing, and advocating for these traditions.

You did not mention Maroon heritage. That is where Gales Point’s Sambai emanates from. It is not necessarily Creole, but rather, the purest form of West African in the Americas..Belize is one of only three countries in the Americas where there are Maroons (the others being Suriname and Jamaica).

I like it. I’d never really heard Kriol culture mentioned until I went to a museum in Crooked Tree about it. I’d lived in Belize for 12 years…traveled a bunch and had never really thought about it. Like you said…it’s kinda everywhere and hard to pinpoint. In San Pedro, there is a strong sense of Mestizo and everyone knows about Garifuna. Interesting article! I love the Belize River basins unique history…from the Cricket teams to the food…you inspired me to learn a bit more.